Auteur Directors: Any American Women?

by Maria Giese

In 100 years of cinema, no American woman director has ever been invited to join the pantheon of international auteur directors. Non-American women directors like Andrea Arnold, Jane Campion, Liliana Cavani, Claire Denis, Marleen Gorris, Agnieszka Holland, Lynne Ramsay, Agnes Varda, Lina Wertmuller among others– directors with bodies of work that match those of their male counterparts– hardly exist in America, with the possible exceptions of masterful experimental directors, Maya Daren and Nina Menkes.

Kathryn Bigelow, who could be a top contender for American auteur director, had to leave America, after six years of unemployment, to seek financing in Europe, and is still not included with men among auteur directors. Other successful women directors who have made both commercially and critically successful features in America are mostly film and TV stars: Drew Barrymore, Jodie Foster, Penny Marshall, Barbra Streisand, Betty Thomas, to name a few. These directors have done fine work, but mostly within the confines of the studio system where, just once in a blue moon, a director like Nora Ephron, Catherina Hardwicke, Mimi Leder or Nancy Meyers can carve a niche.

The question arises, who are the American women directors whose films reveal the work of an auteur director? One could jump in with dozens of directors, from Anders, Arzner, Bigelow, Cholondenko, Coppola, Coolidge, Dash, Dunham, Hardwicke & Holofcener— just to start through the alphabet, but like Bigelow, none of these excellent directors is embraced as an auteur by the paternalist American film establishment.

In the United States less than 5% of feature films are directed by women, so for a director to emerge who is not already a women celebrity, is virtually impossible. Women directors usually make just one film before getting taken down early in the pipeline: if it’s not the misogynistic Hollywood studio system that expels them, their films are given paltry distribution and P&A budgets, or sometimes gender-biased critics comprised of over 80% males will likely taint their reviews.

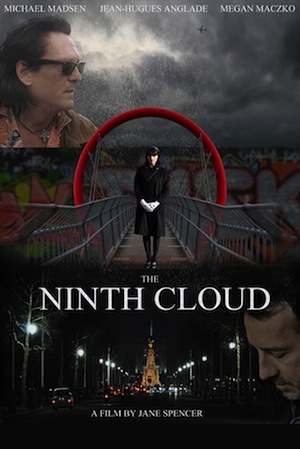

One perfect example of a very fine American woman director whose body of work clearly distinguishes her as an auteur director is Jane Spencer. Jane Spencer is the director of the beloved low-budget indie feature Little Noises that premiered at Sundance some years ago to ecstatic reviews— and enamored audiences, and of Faces On Mars, which premiered in Europe at Solothurn. Her new film, The Ninth Cloud, which is being repped for distribution by Shoreline Entertainment is a dreamy, surreal marvel, which could do very well on the 2014 international festival circuit.

For Spencer, who dreams big, but must keep her budget small, ingenuity is the name of the game. As she says, “My dream as a kid was to direct big David Lean-style epics, so working within the framework I can create, I try to imbue my indie films with giant, epic themes.” Imagine if women directors like Spencer were afforded the budgets and opportunities to realize their immense talents for creating epic, visionary films.

I have always thought that film directors are like alchemists and magicians, but women directors have to be able to master another kind of magic as well: film financing in a void. Most women directors must cobble their production budgets together in any number of mysterious ways, and I wanted to know how Spencer had done it again. How did she succeed in making yet another wonderful feature film? How had she found the money?

I have always thought that film directors are like alchemists and magicians, but women directors have to be able to master another kind of magic as well: film financing in a void. Most women directors must cobble their production budgets together in any number of mysterious ways, and I wanted to know how Spencer had done it again. How did she succeed in making yet another wonderful feature film? How had she found the money?

Spencer answered the question with a question: “In an industry so difficult for women directors, how can any women director raise the money to make a film? You are basically forced to think outside the box. You just can’t give up. You try all the traditional methods: submit your script to actors, agents, studios, production companies, get it to friends in the business. They almost always lead to dead ends.

“So, finally, you go out and find it dollar-by-dollar— private equity from investors who like the project obviously, private loans you— yourself— take out. You get everything on the cheap, but keep the quality; get everyone to do you favors, but make sure they ‘get it’ and believe in the film. That’s the only way an American woman can make an indie feature film.”

Spencer shot The Ninth Cloud on super 16mm. Having a film camera instead of shooting digitally gives The Ninth Cloud a look that is simultaneously both very modern and nostalgic. As Spencer says, “It allows for the documentary, free-camera look I wanted to capture inspired by films like The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, Darling, and Billy Liar. These low-budget 1960’s British kitchen sink films were an inspiration for Spencer, her Production Designer/Producer Richard Hudson and her DP, Sam Mitchell. She goes on, “I wanted the film to express an impressionistic vision of Zena’s (the main character) world.

In the film, in which we follow the dreamy, strange Zena, through what turn out to be her final days….Spencer glorifies the vulnerable Zena through a nuanced appreciation for her ability to “see.” Keeping her indie budget low, Spencer uses inexpensive, old film technology to record her character’s fleeting, childlike, and magical perception of the world around her—and it works beautifully. The film captures the elusive, dream-like moments, as fleeting as a painter’s sudden awareness of reflected sunlight glancing off rippling water– impressionism– that gets at the essence of art, and is the very reason we revere our great male “Masters of Cinema.”

As Spencer puts it: “I wanted to depict, from a women’s perspective for once, the victorious dreamer. One doesn’t have to accept ‘reality’ to live a meaningful life. Whatever your journey is—stay with your dream. You cannot be dissuaded by pressure to conform to social norms, systems, or institutions that tell you ‘cannot’ because it’s ‘unrealistic’ or ‘impossible.’”

We all know that numerically, becoming a female film director in America is virtually impossible— as former DGA president, Martha Coolidge says: “like winning the lottery.” It’s a bizarre anomaly that America, the leader of the free world, virtually excludes women from its most culturally influential global export—media. Hollywood’s level of support of women film directors is among the worst in the world, something that is now accentuated by the recent drafting of international charters that promote the gender equity among women directors in many countries outside the United States.

However, making feature films that move and inspire audiences is Spencer’s quest and she has not been dissuaded by statistics. She says: “This was a very, very difficult film to finance. We had some wonderful equity investors, our own company invested a lot of the money– especially for post, and there turned out to be not many pre-sales. It was very much patchwork financing, very hard, and we filmed it over the space of a year, in sections, because budget-wise, we had to.”

Even after her critical success at Sundance her studio meetings were difficult. After years of struggling to get financed out of L.A., Spencer happened to move to Europe for personal reasons, and immediately had much better luck.

“We got it done– though at times we didn’t think we would. We started financing in 2008 when the financial crisis happened, so some of our financiers fell out. Our wonderful male lead at the time, Guillaume Depardieu, whom I adored, died of pneumonia on a set in Romania. I really wondered if this film would happen – for a moment. But then the producers and I got right back up on our feet and started financing it again. We found the amazing lead actress Megan Maczko in a play on London’s West End….Michael Madsen, who is great in the film—so sympathetic — playing a dishwasher/poet (instead of a guy with a gun) – was lovely and stayed with the project….and we got the great French actor Jean Hugues Anglade onboard – We got right back up on our feet and started financing it again. By 2011 we had finished shooting. We’ve been in post for two years: all of 2012 and much of 2013.”

All the hard work has been well worth the effort. Spencer’s multi-layered film is woven with themes of Djuna Barnes and Baudelaire and traverses the landscapes of Marcel Carne and Antonioni. What makes the film so exceptional is how freshly these motifs have been re-imagined through this director’s effortless lens. The Ninth Cloud is at once tender and deeply moving, yet it manages to reject sentimentalities while glorifying its heroine and uplifting the audience.

Will women directors like Spencer ever join the pantheon of international male auteur directors? That depends upon the whether or not the U.S. cultural consciousness evolves to finally embrace gender equity in our nation’s most influential global export—media. Only then will women directors get the budgets and opportunities to test their metal and take their rightful places in the annals of American cinema.

The Ninth Cloud will be opening in select theaters internationally starting 2014.

Please visit The Int’l List of Living Women Directors: http://www.womendirectorsinhollywood.com/

Marie Giese is American feature film director, a writer, a member & elected Director Category Representative for women at the DGA. She graduated from Wellesley College and UCLA graduate film schooland co-founded the foremost international web forum for political action for women directors (VISIT HERE). An activist for parity for women directors in Hollywood, she is in development to direct two feature films Rain and Treasure Hunt.

View Article